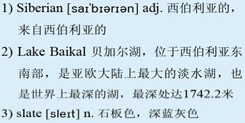

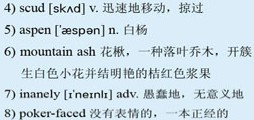

穿越西伯利亚之旅 Trans-1)Siberian Express A Window on Russia

文字难度:★★★☆

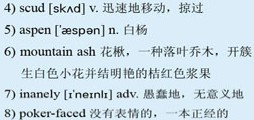

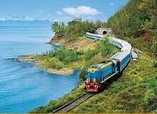

Never did I dream I would experience the first few miles of the Trans-Siberian railway standing on the locomotive. Smiling through the raindrops, I peered across 2)Lake Baikal, which alternately glittered in sunshine and darkened to 3)slate as clouds 4)scudded across the sky. The leaves of 5)aspen trees lining the lakeshore fluttered in the breeze and Siberian roses and the red berries of 6)mountain ash flashed by as we approached the 33 tunnels that break this spectacular stretch of railway, blasted from cliffs that rise sheer from the lake. Grinning 7)inanely at the 8)poker-faced driver of the Trans-Siberian, I filled my lungs with clear Siberian air.

我从来没有想过,在穿越西伯利亚的火车之旅中,最初的几英里行程我居然会站在火车头上。我微笑着透过雨帘远眺贝加尔湖,湖面时而在阳光下闪闪发光,时而又因乌云密布而呈深蓝灰色。湖边成行的白杨树在微风中摇曳,西伯利亚玫瑰和红色的花楸浆果一闪而过,我们驶进了打断这一程风景的33号隧道,这是一条从湖边拔地而起的山崖上打通的隧道。我一边对着那一本正经的列车司机咧嘴傻笑,一边尽情呼吸着西伯利亚的清新空气。

我从来没有想过,在穿越西伯利亚的火车之旅中,最初的几英里行程我居然会站在火车头上。我微笑着透过雨帘远眺贝加尔湖,湖面时而在阳光下闪闪发光,时而又因乌云密布而呈深蓝灰色。湖边成行的白杨树在微风中摇曳,西伯利亚玫瑰和红色的花楸浆果一闪而过,我们驶进了打断这一程风景的33号隧道,这是一条从湖边拔地而起的山崖上打通的隧道。我一边对着那一本正经的列车司机咧嘴傻笑,一边尽情呼吸着西伯利亚的清新空气。

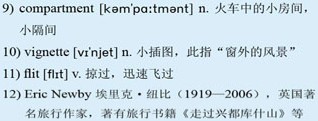

Six days later, the exhilaration of that first day is a faint memory and I am settled comfortably into daily train life. I’ve grown accustomed to staring wide-eyed through the windows of my 9)compartment, the corridor and the dining car, hungrily trying to take in all the 10)vignettes that 11)flit past the windows. However, as 12)Eric Newby wrote when he traveled on the Trans-Siberian in 1977: “There are so many questions that have to remain forever unanswered when one travels by train.” And it’s precisely the mysteries beyond the window that make train travel so appealing, particularly with this journey along the world’s third-longest single continuous railway service.

六天以后,出发首日的愉悦已成淡淡的回忆,我已经适应了舒适的列车日常生活。我习惯了睁大眼睛去看车窗外的风景,无论是在包间里,过道上,还是在餐车里,我都如饥似渴地把窗外掠过的如画风景印入脑海。然而,正如埃里克·钮比1977年在穿越西伯利亚的火车之旅中写道:“当人们乘火车旅行时,有诸多问题会成为永远难以解答的迷。”正是车窗外的神秘世界使乘坐火车去旅行变得如此令人心动,特别是行走在这条世界第三长的单段连续铁路线上。

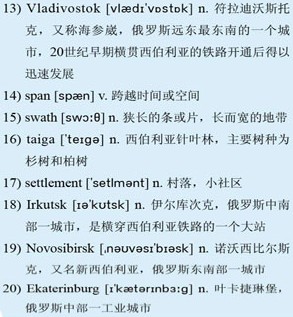

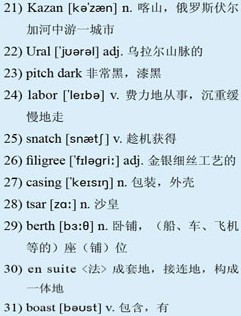

Built between 1891 and 1913, the Trans-Siberian Railway stretches for 5,753 miles from Moscow’s Yaroslavsky terminal to 13)Vladivostok on the Pacific Ocean. The journey 14)spans seven time zones and as a passenger you soon grow accustomed to having two clocks on the train and station platforms—one showing Moscow time, which dictates life on board, the other displaying local time. I am traveling east to west, which means I gain more time every day to admire the scenery as we traverse 15)swathes of dense 16)taiga, vast wheat fields and pretty aspen forests, and pass tiny rural 17)settlements and cities, ancient and modern.

穿越西伯利亚的铁路建于1891年至1913年,从莫斯科的雅洛斯拉夫斯基火车站到太平洋沿岸的符拉迪沃斯托克,全长5753英里。铁路全程横跨7个时区。作为旅客,你很快就会习惯在火车上和站台上有两个时钟——一个显示莫斯科时间,这是火车上日常生活遵循的时间,另一个则显示当地时间。我是由东向西旅行,这就意味着我每天都可以多“赚”一些时间来观赏风景,我们沿途穿过茂密的针叶林,宽广的麦田和美丽的白杨林,经过小小的乡村村落,以及或古老或现代的城市。

I am covering a relatively short stretch of the railway—a mere 3,188 miles—from the shores of Lake Baikal to Moscow. Since boarding on the shores of Lake Baikal six days ago, I’ve visited the city of 18)Irkutsk, 19)Novosibirsk, the beautiful city of 20)Ekaterinburg, and 21)Kazan. I’ve also crossed the 22)Urals—albeit in the 23)pitch dark and in the comfort of the dining car—and passed effortlessly from Asia to Europe, experiencing the changes in people, countryside and architecture between the two continents. I’ve spent enough time on the train to be familiar with her noises and movements. I feel her effort as she 24)labors uphill or shifts awkwardly round corners, and find the 25)snatched glimpses of the tracks underneath my feet as I walk between carriages and the noisy clatter of metal on metal reassuring rather than merely alarming. I can now also mispronounce sufficient Russian phrases to greet the train staff as I squeeze past them on my way to the restaurant car and to ask Sergei, my carriage attendant, for a cup of tea. This he delivers to my compartment in a podstakannik, a large, traditional tea glass with delicate 26)filigree 27)casing.

我的旅程相对短一点——只有3188英里——从贝加尔湖滨到莫斯科。自从六天前在贝加尔湖边上车以来,我已经参观了伊尔库次克市和诺沃西比尔斯克市,探访了美丽的叶卡捷琳堡,以及喀山市。我还穿越了乌拉尔山脉——尽管外面一片漆黑,而我身处舒适的餐车里——毫不费力地从亚洲来到了欧洲,感受到了两片大陆上的人物、景致和建筑之间的差异。在火车上待了足够长时间之后,我已经熟悉了其声响动静,我能感觉到她倾尽全力地爬坡,又笨拙地拐弯。在走过车厢连接处时,我能趁机瞥一瞥脚下的钢轨,金属撞击发出的咔哒声与其说是扰人心神,不如说听着让人感觉心安。现在,当我到餐车去,与列车员擦肩而过时,我那发音不准的俄语已经足够应付与他们打个招呼,还可以向我的车厢服务员塞盖要一杯茶。他用“泡兹塔坎尼克”装了一杯茶送到我的包间。那是一种传统的大玻璃茶杯,杯上带有精致的金银丝纹饰。

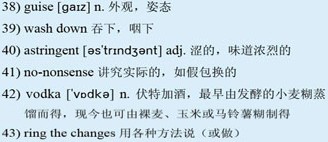

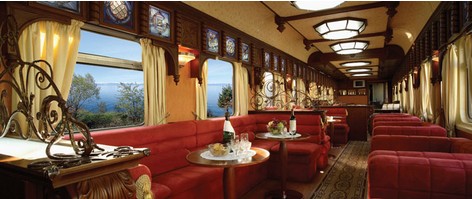

I am fortunate to have the luxurious space of a 28)Tsar’s Gold two-29)berth compartment, one of six in my carriage, complete with an armchair, table, sofa—which Sergei folds out each night into a large, comfortable bed—wardrobe and 30)en suite with a surprisingly good shower. All compartments 31)boast a small radio, which we’re encouraged to leave on, for it offers announcements about forthcoming stops as well as local music. So, between bursts of thigh-slapping 32)Cossack music and melancholic 33)Slavic singing, a voice crackles out in Russian, German and English with announcements such as: “We will be arriving at 34)Zuma at 4:32pm Moscow time. The train will stop for seven minutes.” During these brief halts, passengers stretch their legs on the platform, snatch puffs on cigarettes and stock up on snacks and essentials from the ubiquitous Russian 35)kiosks. The glass fronts of these tiny structures are crammed with an array of biscuits, jars of pickled vegetables, fish, eggs and who knows what else: cigarettes, soap, matches—36)you name it. Almost invisible to the eye, the kiosk’s 37)proprietor peers from a small window in the center of this sea of products, through which an arm extends to take your rubles and deliver your purchases.

我有幸住在“沙皇金色双卧铺包厢”的豪华包间里,这样的包间一节车厢里有六间。包间里有扶手椅、桌子和沙发。到了晚上,列车员塞盖会将沙发拉出来,变成一张舒适的大床。包间里还有衣橱和一套很棒的淋浴设施。每个包间都配有一台小收音机,列车员告诉我们最好把收音机打开,因为除了播放当地音乐外,它还会播报列车前方即将停靠的车站。于是,在富有节奏的哥萨克音乐和悲伤的斯拉夫歌曲之间,一个声音用俄语、德语和英语进行广播:“我们将于莫斯科时间下午4点32分到达祖玛,列车将停靠7分钟。”在这些短暂的停车时间里,旅客们跑到站台上舒展一下腿脚,抽一支烟,或者到无处不在的俄罗斯杂货摊上采购食品和生活用品。那些杂货摊的玻璃门面前堆满了各种饼干、罐装泡菜、鱼、鸡蛋,还有一些说不出名称的货品:香烟、肥皂、火柴……应有尽有。小摊老板从这些货品当中一个小小的窗子朝外观望,你几乎看不见他,而他从这个窗子伸出手来拿走你的卢布,并递出你要的商品。

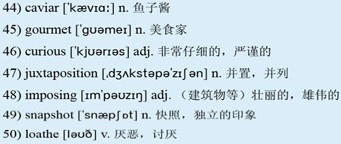

Food on board wasn’t all about platform snacks. The train has two attractively decorated dining cars, one at the front and one at the rear, to which passengers are assigned on arrival. Meals, though, are not always a culinary highlight, consisting often of dense brown bread, pickled soups, cabbage, potatoes and meat in various 38)guises, 39)washed down with acidic wine and 40)astringent, 41)no-nonsense 42)vodka. To 43)ring the changes, some of us stock up on 44)caviar, cheese, smoked fish, fresh bread, honey, yogurt and dried fruits. Meals in the dining cars, however—while not always of 45)gourmet quality—are a social highlight of the journey. Particularly on the one full day spent traveling, when the dining room is the venue for Russian language lessons, history talks, extended card games and caviar and vodka tasting.

列车上的食物跟站台上的快餐有所不同。列车配有两节装修精致的餐车,分别位于列车头尾,旅客们在上车时就已经被分配好到哪个餐室就餐。餐食并非总能达到大厨特推的标准,常有的食物是厚实的黑面包、泡菜汤、卷心菜、土豆和各种肉类,配有酸酒和味道浓烈、如假包换的伏特加酒。为了换换口味,我们有人自带了鱼子酱、奶酪、熏鱼、新鲜面包、蜂蜜、酸奶和干果。在餐车里用餐,尽管里面的食物够不上美食家的标准,却是旅途上社交的好机会。尤其是在经历了一整天的旅程之后,人们可以聚在餐车里一起学习俄语,谈论历史,打打牌,品尝鱼子酱和伏特加。

These experiences of Russia’s people and cities, and the diverse scenes one glimpses from the train, are what make a journey along the Trans-Siberian Railway so distinctive—whether it’s the 46)curious 47)juxtaposition of our hostess’ teddy bear collection and her husband’s gun collection in their home near Lake Baikal; a bride and groom posing for photographs against a wall of 48)imposing bronze portraits of revolutionaries in Ekaterinburg; or two glamorous women dressed in leather and fur driving their new BMW past an old man pushing a wooden truck loaded with vegetables in Novosibirsk. Such 49)snapshots come together to create a unique collage of contemporary Russia. Sharing these experiences over tea and vodka in the dining car with my new friends makes this journey particularly special and I know I’ll be 50)loathe to leave them in Moscow.

These experiences of Russia’s people and cities, and the diverse scenes one glimpses from the train, are what make a journey along the Trans-Siberian Railway so distinctive—whether it’s the 46)curious 47)juxtaposition of our hostess’ teddy bear collection and her husband’s gun collection in their home near Lake Baikal; a bride and groom posing for photographs against a wall of 48)imposing bronze portraits of revolutionaries in Ekaterinburg; or two glamorous women dressed in leather and fur driving their new BMW past an old man pushing a wooden truck loaded with vegetables in Novosibirsk. Such 49)snapshots come together to create a unique collage of contemporary Russia. Sharing these experiences over tea and vodka in the dining car with my new friends makes this journey particularly special and I know I’ll be 50)loathe to leave them in Moscow.

那些和俄罗斯人们的交往,那些城市,那些从车窗外看到的异彩纷呈的风景,使得穿越西伯利亚的火车之旅如此与众不同——无论是在贝加尔湖边看到的一位女房东一丝不苟地陈列其泰迪熊收藏以及她丈夫收藏的枪支;还是在叶卡捷琳堡看到一对新婚夫妇在雄伟的革命者铜像前摆姿势拍照;还是在诺沃西比尔斯克市看到两位穿着毛皮大衣的美女驾驶着簇新的宝马汽车经过一位费力推着装满蔬菜的木板车的老人。这些影像拼凑在一起构成了一幅独特的现代俄罗斯拼图。在列车的餐车里,我和新朋友们一边品尝着茶和伏特加,一边分享着这些经历,这让此次旅行尤为特别。我知道,等到了莫斯科,我会舍不得离开他们。